My career in architecture has been enriching to me. But unfortunately, saying that in a public forum is very risky.

That’s because I am not a licensed architect.

Yet, I have had a rewarding career; what a conundrum.

- Who governs architecture?

- States govern architecture, interior design, and engineering, either through a practice act or a title act.

- Now for the meat and potatoes of this article, the exempted activities.

- In Florida, where I've done the lion's share of my work, the only activities exempted in that essential paragraph, or series of subparagraphs, include,

- But in Texas, the exempted building types are much more significant,

- In California, exempted activity is severely limited too,

- In Oklahoma, the exemptions are the most liberal,

- Where is this information found?

It’s no wonder those of us working in the industry using the statutory exemptions seem to hide our light under a bushel meekly rather than letting our light shine brightly.

I assure you, building design professionals across our nation are successfully marketing their services, and you can too.

But before you read any further, I am not an attorney. So, what I’ve written is NOT advice. But I have been accused of breaking the law on multiple occasions.

Start your building design business right now:

–> Take the video course <–

Who governs architecture?

Each state and the District of Columbia have its individualized statutes.

Although most are relatively similar, some are very distinctively different.

Just because you may be legally practicing a particular discipline in architecture where you currently reside doesn’t mean you can perform the same services in other states. But the exciting thing is even without an architectural license, you can design something in almost every state.

Over the past 38 years, I’ve been responsible for the design of projects in at least 12 states. Primarily single-family homes, and a few townhouse projects, in Florida, California, Texas, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Massachusetts.

Also, I’ve done remodeling projects in Arizona, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, DC.

Meanwhile, Colorado accepted me to take the architectural registration exam, or ARE, which happened about 18 years ago. However, I never started the process.

Had I become an architect, I most likely would have been required to apply for reciprocity in each state I’ve offered services.

Still, by taking advantage of the statutory exemptions, I’ve been able to cross state lines freely, without any paperwork, and mostly without fear of prosecution. But I had to research what kind of work would be allowed and how to represent myself in each state.

States govern architecture, interior design, and engineering, either through a practice act or a title act.

They also do so either by licensure or registration.

A practice act means that you must be licensed or registered to practice.

A title act refers to being licensed or registered to call yourself by a title.

Examples:

- a registered architect,

- a registered interior designer, or

- a licensed engineer.

Some aspects of a registration or licensure act are common from state to state.

- A definition of the profession,

- The body that oversees the profession,

- The educational, experiential, and testing requirements,

- Exempted activities within the profession,

- How to behave as a professional,

- The process for renewing, and

- The penalties for misbehaving.

The definition of the profession usually includes pretty much any activity you can think of that is even remotely possible, which are design-related activities, such as,

- Planning

- Preliminary study designs

- Drawings and specifications

But then the statutes can also include things you may have never thought of, such as,

- Job-site inspection

- Administration of construction contracts

- Teaching architectural courses

- Investigation

- Consultation

- Evaluation

- Plan review

- Bid document prep

- Advice

- Coordination of technical consultants

The body that oversees the profession is usually titled something like Architectural Registration Board or Professional Licensing Board.

Some states are creative, such as “The Arizona Board of Technical Registration.” The board typically consists of members of the profession appointed by the governor or some legal entity within the state.

When I say members of the profession, I’m referring to those licensed or registered.

Those practicing the exempted activities aren’t technically a part of the act and therefore are not viewed as “members of the profession.”

Some states have one or more “public members” serving on their boards, which are seats to be filled by consumers of the profession.

One license I’ve obtained is a general contractor’s license. But even though a builder is an exact consumer of our practice, that too might be a tough sell for a public member seat.

I have observed that those nominated by an association fill most professional member seats. In the case of an architectural registration board, the American Institute of Architects, or AIA.

The public member positions are usually filled by a Tom, Dick, or Harriet contributing to a political campaign.

Therefore, remember that if you should ever find yourself defending your actions at a board hearing, most of those sitting at the table and deciding your fate will most likely be architects. But don’t let that intimidate you.

You are just as much a design professional as they are; you have different rules to follow.

Every state has an educational requirement to qualify to be an architect. Most require a five-year degree in architecture at a school accredited by NAAB, the National Architectural Accrediting Board, which is a part of the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards, or NCARB, which also is the body delivering the national ARE.

Some allow some form of experiential equivalent. Those that come to mind are California, Texas, Colorado, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and New York. I chose to apply to Colorado because I’m from Florida and like mountains.

At the time, I was managing director of an architectural firm in Palm Beach, and occasionally, we would design a custom home in Colorado. And I like the mountains.

To qualify using experience, I had to complete the same Intern Development Program, or IDP, form that the college grads have to complete; only my application had to establish 3 to 4 times more experience, basically ten years in my case.

I could only apply to be a general contractor to one of the ten. The other nine had to be under the responsible control of an architect.

Owning and operating a residential or building design firm for ten years or more does not qualify as experience. For the benefit of those of you as old as I am.

What used to be referred to as IDP is now AXP, which stands for Architectural Experience Program.

Start your building design business right now:

–> Take the video course <–

Now for the meat and potatoes of this article, the exempted activities.

Typically, all states exempt government employees; you can be the “Architect of the Capitol Building” and not be an architect, technically.

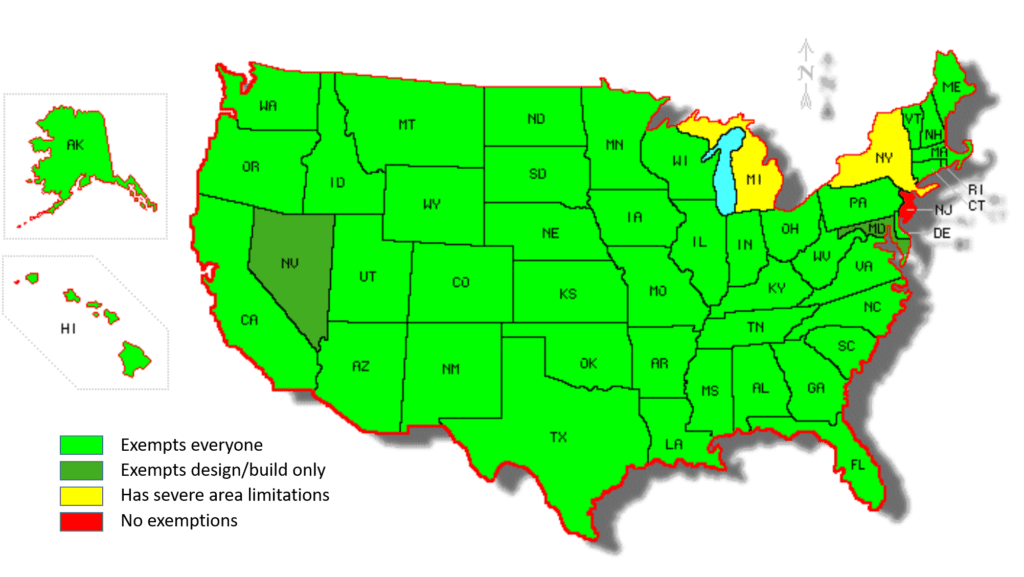

All states typically exempt the employees of architectural forms, too. All states but ONE, New Jersey, have a paragraph that exempts “those who prepare the design and construction drawings for” certain building types and occupancy uses.

Nevada is the only state with licensure for residential designers but exempts design/build firms from licensure in residential design. Maryland is the only other state that only exempts design/build firms.

In Florida, where I’ve done the lion’s share of my work, the only activities exempted in that essential paragraph, or series of subparagraphs, include,

- Florida §481.229

- Farm buildings

- One- or two-family residences or outbuilding

- Townhouse

- Other buildings costing <$25k (except school, auditorium, or governmental/public buildings)

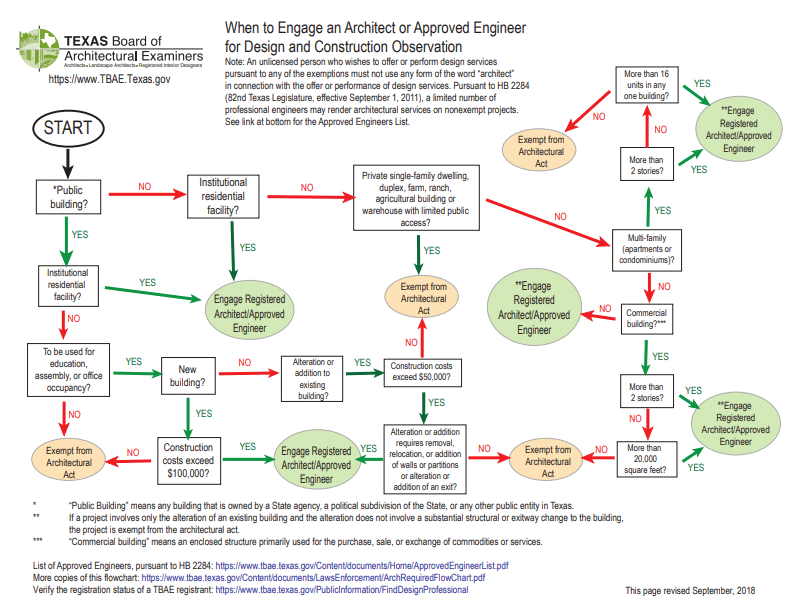

But in Texas, the exempted building types are much more significant,

- Texas Occupational Code Title 6, Subtitle B, Chapter 1051.607

- Farm buildings

- One- or two-family residences or outbuilding

- 16-unit multi-family buildings 2-stories or less

- Commercial building 20,000 SF and 2-stories or less

- Warehouse with limited public access (no reference to a size limitation)

In California, exempted activity is severely limited too,

- California Business and Professions Code, Division 3, Chapter 3, §5537

- Farm buildings

- One-family dwellings or outbuildings, wood frame, and 2-stories or less

- 4-unit multi-family buildings, wood frame, and 2-stories or less

I believe that the 4-unit multi-family buildings section includes a reference to being able to do clusters of 4-unit buildings on the same property.

Therefore, 100 units could be developed without an architectural license if the project is 25 four-unit buildings up to 2 stories in height.

In Oklahoma, the exemptions are the most liberal,

- Oklahoma §59, Section 46.21b.C

- Any building with an occupancy load of 50 or less and 2-stories or less (except A-2, A-3, and Group E)

- Hotels and motels up to 64 units and 2-stories or less

- Group B up to 100k SF and 2-stories or less

- Group M up to 200k SF and 2-stories or less

- Groups U, F, H, S, R2 (up to 32 units), R3, and R4, unlimited in size but limited to up to 2-stories

- Government buildings up to $158k and 2-stories or less

- All incidental or appurtenances associated with the above.

Where is this information found?

Each architectural board’s website links to the statute and, in some cases, to the state’s professional codes.

Texas has a handy-dandy flowchart, almost in the form of an infographic, which is a beneficial tool for navigating your way through the exempted activities or giving to a client to communicate that you are practicing legally visually.

Another handy tool, which is provided by the American Institute of Building Design, or AIBD, is ArchitectureLaws.com. For now, it’s merely a downloadable PDF. We hope to develop the URL into a website.

Meanwhile, the PDF provides the contact information and website links to each state’s architectural board.

Remember, sometimes the URLs are changed, and AIBD is not conveniently notified by the state when they do that. So if you find broken links, please get in touch with AIBD at info@AIBD.org or 1-800-366-2423.

As long as you prepare schematics, working drawings, and specifications and perform job site observations for those buildings specifically exempted from the act, you are entirely within your rights, regardless of where you live. It’s about project location.

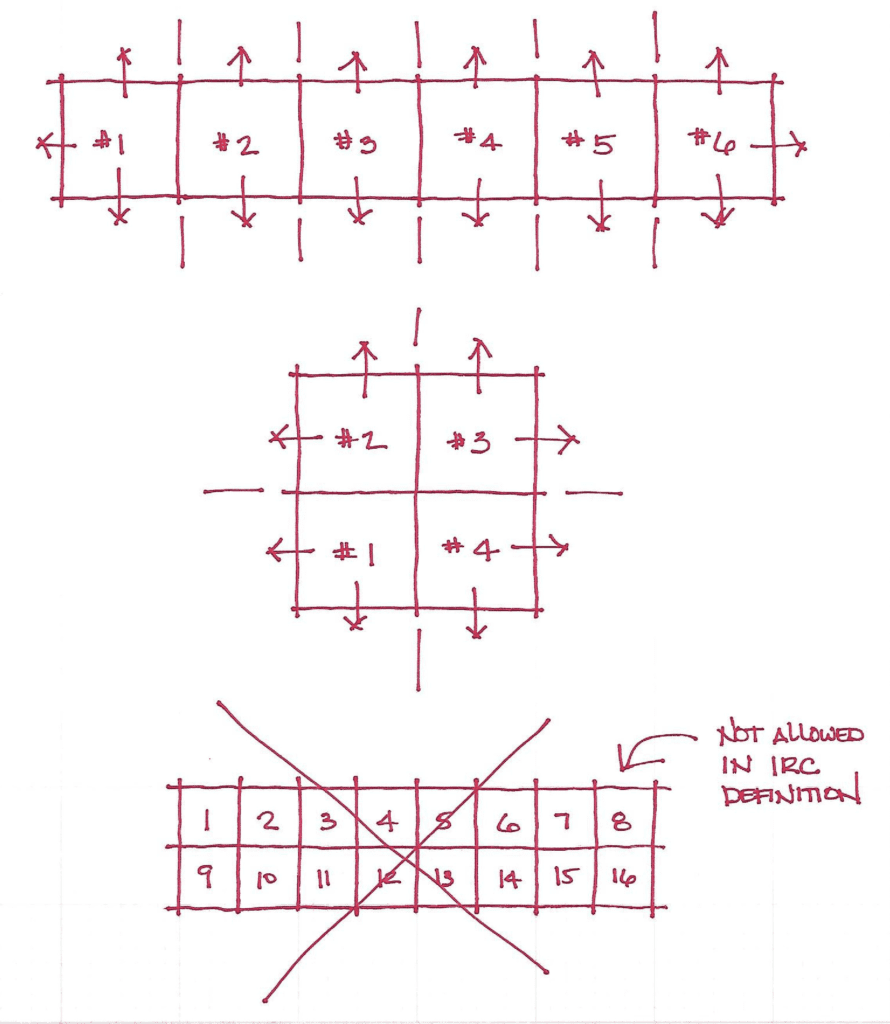

Recently, something that seemed clear is now becoming fuzzy due to interpretations by the architectural registration boards. I’m referring to townhouses.

You must also look closely at the exemptions to determine if they include Duplexes or two-family dwellings. For example, in Oregon, the architectural board considers them multi-family, so they are not exempted buildings.

However, up until recently, they found townhouses to be single-family dwellings. Now, they have a different opinion.

According to the International Residential Code (IRC), to qualify as a single-family dwelling, townhouses must be arranged side by side, in a quadruplex formation, be continuous from foundation to roof, and be fully open on two sides.

Therefore, townhouses designed using the IRC should also be exempt in states where single-family residences are exempt. But that doesn’t always seem to be the case.

Over the past five years, two states have revised that paragraph of their exemptions to specify that townhouses are single-family dwellings.

In the past couple of years, similar legislation was attempted in Minnesota. The bill was altered in a way that caused it to focus on fire sprinklers and not the definition of a townhouse.

This year legislation influenced by the Alabama Home Builders Association, SB 168, was sponsored and introduced but sat in committee the entire legislative session.

Oregon is another state with a newly adopted interpretation in effect. In 2018, the AIBD and the National Association of Home Builders, referred to as NAHB, passed resolutions supporting the efforts to fight this issue nationally.

As a side note, if you’re interested in keeping track of what’s happening at your statehouse, one site I use is OpenStates.org. It’s a free site that was created by hackers as a result of a weekend hackathon.

At OpenStates.org, you choose your state and search keywords. It will list all the bills submitted with your keyword included.

When you click on the bill number, you’ll find out where the bill currently sits on the path to becoming a law, as well as the bill’s sponsor and contact information for all the legislators.

So, townhouses are a tough one. It could be that you’ve been designing them without a license for years, but the next project could get flagged and rejected by the local building department. That event usually only gets you into hot water with your client, but it could be considered “acting as an architect.”

In that case, it could be more of a problem to resolve. But if the interpretation only comes from the building official, I encourage you to research the statutes, know the law, stand your ground, and refute it. That’s not always successful, but you’d be surprised how often it is.

AIBD is also here to speak on your behalf when it’s appropriate.

Exemptions are not the only other way to practice architecture without being a licensed architect legally. There is a good chance your state has a provision for a corporation to offer architectural services by being “qualified” by an architect licensed in that state.

The state may require that the architect be a partner, that a certain number of architects be involved, or that the qualifying architect is a principal officer. And it might be that the state only requires the qualifying architect to be a key employee.

For any of these arrangements, you should seek the advice of an attorney and possibly an accountant. Research the correct way to name your corporation.

You may have to call your company Fictitious Name ArchitectURE, not Fictitious Name ArchitectS (capitalization of the letters added for effect). The latter might only be acceptable if EVERYONE in the firm is an architect.

One of the classic examples of this is Michael Angelo Gideo in Plano, Texas. He specialized in custom-designed backyards. His company installed swimming pools, built outdoor fireplaces and patios, put up decks, and tackled landscaping projects.

The company, Backyard Architect, had a website at backyardarchitect.com. You probably know where I’m going with this, so I’ll take this opportunity to let you know that backyardarchitect.com is for sale.

The Texas Board of Architectural Examiners discovered that Gideo is not, and has never been, a registered architect in Texas, nor is his company qualified by a registered architect.

By Texas law, one of two conditions is to meet if the term “architect” or “architectural services” is used in a business name.

So in July 2009, an administrative law judge advised the board to impose a penalty against Gideo of $200,000. That’s $5,000 a day—the highest penalty the board is authorized to assess—for every 40 days (or longer) that Gideo had violated the law.

How many times have you heard of a “system’s architect?” I Googled it and got 192 million results in three-quarters of a second.

Why aren’t the architectural licensing boards going after them? I don’t know.

Maybe we should start filing some complaints.

By the way, the boards don’t require that you be licensed or registered to file a claim. They all have a link on their websites to do so. That makes it very easy for an investigation to begin, whether warranted or not.

So what happens when a complaint is filed against you with the licensing board?

- They determine if the claim falls within their legal authority.

- If it does, they may conduct an investigation. An investigator will act as an impartial, fact-finding third party. The length of time an investigation takes depends on the current caseload and the case’s complexity.

- After gathering all the facts, they evaluate the information.

- If the evidence doesn’t show a violation of the laws, they dismiss the case.

- If a violation has occurred, they may recommend disciplinary action, such as a reprimand or fine. In the case of someone licensed, a license suspension or revocation.

- At this point, you may request a hearing to dispute the decision or, leading up to the discussion, a plea bargain.

A California licensing board member was quoted in Architect Magazine saying, “A decent number” of cases are due to ignorance, “Folks are genuinely not knowledgeable” about the law. However, he adds, “You also get a fair number who know the law and … are operating on the edge.”

An administrator of the Washington state board estimates “right off the top of [his] head” that about 75 percent of violators don’t understand the legal protection of the title or how they’ve infringed on it. The other 25 percent “is more deliberate—and then we pursue appropriate actions.”

In my position, I’ve seen practitioners using creative uses of the word, like in ARC Services, Arch Studio, ArchCon, ArcDesign, and ArcNET; one of my favorites is Archipello. We have a very creative industry. And it very well might be that all these names are legal.

But I feel that if the company is not qualified by an architect, even creative names open the door to problems. Come up with a name that avoids the A-word together. Such as My Name Associates, House Brand, or Super Dooper Design Group.

When you receive a certified letter from the board, it’s up to you to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that you’re innocent, not the other way around. And sometimes, that isn’t easy.

Thanks to a minor technicality, you can be accused of breaking the law even when designing exempted buildings. Like sizing a rafter or a joist. Does that make you an engineer?

Many of you may be designing buildings and performing engineering. As long as it follows the prescriptive measures in the building code, that should be just fine.

I’ve designed additions to Virginia, Maryland, Arizona, and Pennsylvania homes and sized all the beams, rafters, joists, and footings.

I designed a new home in western North Carolina and provided all the structural details.

Granted, that was about 30 years ago, and I don’t think a plan review was involved.

However, anything I’ve done in California and Florida has engaged an engineer to design the foundation, roofs, floors, and beams. The parts of the construction drawings prepared by me include,

- Floor Plans

- Exterior and Interior Elevations

- Roof Contour Plan

- Building Sections

- Electrical Plan and Calculations

- Plumbing Schematic

In Texas, the homes I’ve done included all the structural design except for the foundation. But one could argue hiring an engineer to design the structure in EVERY case.

Many building designers have expressed how well they sleep at night knowing that someone else is responsible for the structural aspects of the design should something go wrong during or after construction.

And others have made the point that they can move on to designing the next project, while some other firm is creating major elements and details of the construction drawings.

I agree with both points. But don’t be the individual who “hires” the engineer.

Let consultants contract with the client and be paid by the client. Structure your services this way to avoid potential claims that you are “acting as an architect” by coordinating technical consultants or “acting as an engineer” by contracting to provide the services “on behalf of” the client.

To wrap up, if you want to design commercial buildings and large multi-family projects, work strictly in Texas or Oklahoma or become a licensed architect.

You might be like me, a high school dropout with some college. But I’ve taken a path that allowed me to document my experience, even though that causes me to be limited in which states I can become an architect. It’s never too late until it’s too late.

Profound, I know. But, I know at least three middle-aged building designers who have returned to school as adults, earned their master’s degree in architecture, completed their AXP, and passed the ARE. Anything is possible when you set your mind to it.

Because of the nature of the architectural laws, AIBD focuses on education and resources for those specializing in single-family residential design and light commercial design.

Start your building design business right now:

–> Take the video course <–

However, the number of engineers and architects joining AIBD seems to be increasing.

I’m surprised at the number of engineers who apply for the Certified Professional Building Designer, or CPBD, designation, which they earn through reciprocity.

AIBD defines you as a building designer if you are the building owner or the person contracting with the owner for the building design and are responsible for preparing the construction drawings.

That’s a pretty broad scope.

Regardless, AIBD is on a mission to build a better building profession, one BUILDING DESIGNER at a time. Let us know how we can help you.