Perhaps the most improbable story of eleventh-hour design is the one about Frank Lloyd Wright and his conception of the renowned Fallingwater.

That design, according to accounts by several of Wright’s Taliesin apprentices, was produced by Wright while the client, Edgar Kaufman, was driving the 140 miles from Milwaukee to Taliesin.

“Wright emerged from his office, sat down at the table, and started to draw.” Apprentice Edgar Taffel recalled, “The design just poured out of him…Pencils were used up as fast as we could sharpen them…Erasures, overdrawing, modifying, flipping sheets back and forth.”

Witnesses agree Wright only worked for about two hours. The first drawings of Fallingwater – floor plans, perspective, and section – were, primarily, the last.

Wright often claimed, “I just shake the buildings out of my sleeves.”

Wow! What an extraordinary story. But not one of an actual ‘Rush Job.”

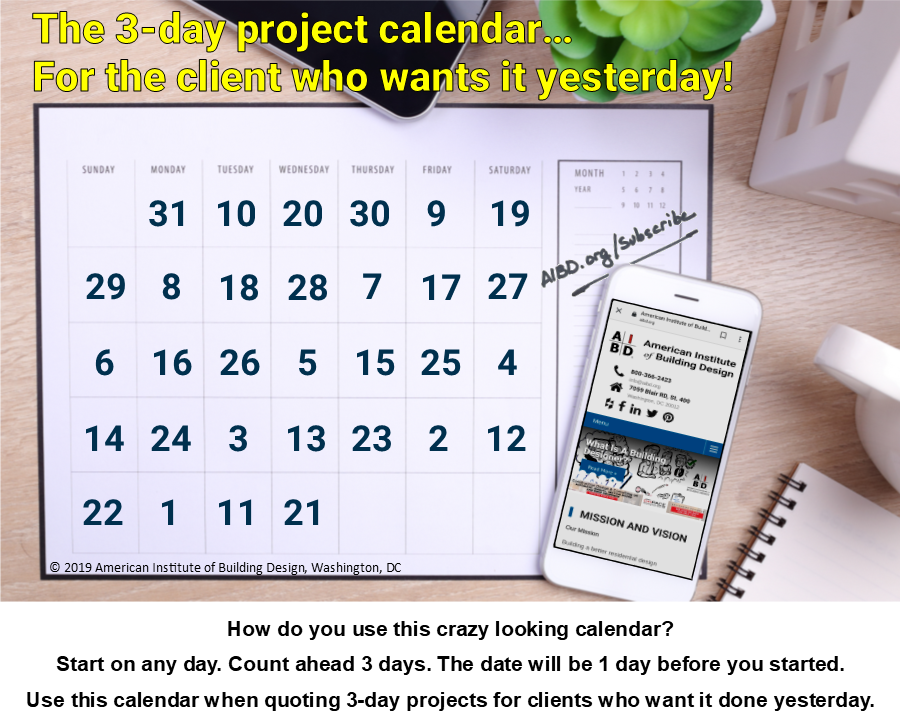

Kaufman had been waiting nine months for Wright to design his home. If it weren’t for deadlines, nothing would get done, right?

However, it’s fair to say, now and then a client with unrealistic expectations may wander into your office. Or maybe it’s an existing client that needs you to, “Do them a favor.”

Either way, good designers know how to set and meet deadlines and when an urgent job materializes, this may be an excellent opportunity for additional income.

- I can only work on one project at a time!

- Play God and manufacture time!

- First things first, know your client.

- But there's only so many hours in a day!

- Rush jobs deserve higher fees or upcharges.

- Won't rush fees damage my relationship with the client?

- Rush is a service, not a fee.

- But what if I don't know how much I should be charging normally?

- Pricing your services isn’t just about the money you want to make, it’s about the quality of life you want for yourself and/or your team.

- → GET MY FREE HOURLY RATE CALCULATOR ←

I can only work on one project at a time!

Surveys performed by AIBD reveal that almost fifty-percent of residential building design professionals work by themselves.

Half of you reading this post are your company’s CEO, CFO, COO, salesperson, production manager, bookkeeper, receptionist, technician, janitor, and occasionally a building designer.

Some designers dread getting the phone call or email requesting work to be completed within a ridiculous time frame. Others thrive on the adrenaline rush and may even own a yacht because of their efforts. Here are some tips on managing an unexpected workload.

Play God and manufacture time!

Darren Hardy is the former publisher of SUCCESS magazine and a New York Times bestselling author. He’s also a CEO coach and a highly sought-after motivational speaker.

In his video training series, “Wickedly Awesome Productivity Tricks,” he lists three ways you can, play God and manufacture time.

1. Invest some time now so that you can manufacture time in the future.

Maybe it’s finally doing the paperwork to set up auto-deposit with your bank or installing and learning the mobile app so you can deposit checks electronically, saving you dozens of trips to the bank.

Or maybe it’s setting up your desk and filing system on a weekend so you can fly faster through the workday.

Maybe it’s creating an orientation manual or training video so the time spent hiring and onboarding new employees are cut in half, and their effectiveness is increased significantly.

2. Get help and delegate.

Yes, you do have to stop or slow down to design the job function and find, hire and train the help, even if you sub-contract.

That is the deposit you make into the compound effect account.

But once made, that deposit compounds quickly and manufactures massive quantities of time you wouldn’t have had otherwise.

3. Leverage the “compound effect” and manufacture time through systems.

Stopping to build the right systems can ultimately set you free.

Countless business owners complain about lack of control or freedom yet in the same breath, discount the value of well-designed systems.

First things first, know your client.

It’s not unreasonable for a design contract with an unusually tight turnaround to be considered, by both the designer and the client, a favor.

Acts of goodwill performed on occasion are admirable. But typically it’s when a healthy and constructive relationship already exists between two parties.

Feel good when you’ve managed your schedule in a way that such a gesture is possible. While at the same time, a “good” client will understand that quality work takes time and needs to be planned for accordingly.

Therefore a reasonable upcharge will be in order.

On the other hand, avoid agreeing to a shortened deadline when signing up a new client. That behavior starts you off on the wrong foot and pretty much establishes unreasonable expectations as the norm, at least for this project.

But there’s only so many hours in a day!

Remember the days of pen plotters? It used to take 45 minutes to an hour to print one page.

It was possible for a comprehensive set of construction drawings to take two to three working days to plot.

Even today, municipalities seem always to like to choose January 1 as a date for instituting a new building code or increase the permitting fees.

At a recent conference, Steve Mickley, AIBD Executive Director, shared a story about just this situation.

“Impact fees were going up next week, and a builder client walked into the office on Tuesday,” Steve begins. “He ordered three or four pre-designed models and wanted to submit them for permitting on Friday. Even if I hadn’t already committed to other projects there just wasn’t enough hours to complete the printing,” Steve explained to the client by counting the pages and the hours.

“Sounds like you need to be able to print faster, how can we make that happen?” The client responded.

It just so happened, Steve had already been shopping for the latest and greatest inkjet plotter, so the brochure was close at hand. “The client pulled out his American Express card, and by the end of the day, we were printing a page every five minutes,” Steve concluded.

The point of the story is, work together. Understand each other’s needs and what the obstacles are. Put your heads, and your resources, together and come up with a solution that works for everyone.

“If you have a problem you can solve by throwing money at it, you don’t have a very interesting problem.” — Anne Lamott.

Rush jobs deserve higher fees or upcharges.

If you’re a part of a network of building designers, such as the American Institute of Building Design, you may have the opportunity to outsource the rush job. Use the extra fees to pay them the same you would normally charge and use the upcharge as your net gain.

Or do the work yourself and be reward (or hopefully you have employees to reward) for working overtime.

In Steve’s prior example, charge more to be able to obtain the technology or equipment necessary to complete the project.

Won’t rush fees damage my relationship with the client?

That depends on the expectations you established in the past.

If you have a clear scope of work that identifies timelines and responsibilities on each side, then it will be clear where this rush job fits in.

Address rush fees upfront when you negotiate a contract, whether it’s a single design contract or a long-term contract with a developer. Especially the latter.

With a strong foundation in place, your client will understand that what your are asking for is a kind of change order.

Reasonable clients expect to pay a rush fee in those cases.

Without a clear scope of work, then you are vulnerable to scope creep. Think of the rush fee as a kind of service to offer your clients rather than something that will offend them.

Sudden changes that need a quick response are an unavoidable reality in the fast-paced businesses.

A rush fee enables you to provide a valuable service to clients in those circumstances. It’s worthwhile to anticipate this issue and to put language about rush fees (and other forms of change orders and overages) into your scope of work so that clients know they can ask for it. You can cover this in the Extra Charges section of your contract.

Here is an example of rush fee wording:

“Client may request additional deliverables beyond this scope at an hourly rate of $_____. Normal turnaround time for first drafts on assigned deliverables is _____. Clients may request rush jobs on new or existing assignments for an additional charge of _____ percent of the hourly rate.”

Rush is a service, not a fee.

The trick is to make a rush fee sound like a service that is available to your clients — not a penalty you are imposing.

For example, how many times have you had a client ask for a “Penalty Clause” in your contract? If you’re late, they incur additional rental fees on temporary housing, carrying costs on the land, and possibly interest on a loan.

That sounds reasonable.

Then doesn’t it also seem reasonable to include a “Bonus Clause”? Once the client establishes what their liquidated damages are for being late, begin the discussion on your bonus for finishing early.

Logically, every day you finish before the established deadline you are “saving” the client the exact same amount they want to charge you for being late, make sense?

But what if I don’t know how much I should be charging normally?

Whether you use hourly pricing, flat-rate pricing, or value-based pricing for your design services, to calculate the total price for a specific project, you need to know your minimum hourly rate.

But where do you start, what do you need to consider when setting your pricing, and how do you calculate an effective hourly rate?

The simplest approach is to divide the salary you want by the number of hours worked each year:

40 hours/week × 52 weeks/year = 2,080 hours

$100,000 desired salary ÷ 2,080 hours = roughly $50 per hour

Unfortunately, it’s not all that simple. The math makes sense, but the thinking behind it is all wrong.

If your goal is to make $100,000 per year and you only charge $50/hour, you’ll soon find yourself in a lot of trouble. What if you want to take a few weeks off throughout the year? You need time for personal development or attending professional conferences.

Think about those tasks you do in your business that aren’t considered “billable.” Not only is your time to be considered in the formula, but there are also expenses to factor in, such as insurance, office supplies, conference registrations, travel, and the list goes on.

Pricing your services isn’t just about the money you want to make, it’s about the quality of life you want for yourself and/or your team.

When setting fees you need to think about total annual company earnings (gross) and total annual income (net), as well as total company profit. Sounds complicated, doesn’t it?

The American Institute of Building Design has a worksheet that simplifies the process. It’s a part of a larger compilation of business forms and templates called, DesignerDocs™. Get started today charging the right fees for your business and charging even better fees to cover other scopes of work, such as rush jobs.

CLICK HERE to download the “Hourly Rate Calculator,” an Excel spreadsheet designed with every business function included and all the necessary formulas pre-programmed.

Once you download the file, there will be instructions on how to use the worksheet, as well as for how to obtain the full library of DesignerDocs™.

2 thoughts on “5 tips on how to profit from “Rush Jobs.””